Into the wild – From Beat Dreams to Mortal Truths

This film feels like a strange fusion of Faust, The Call of the Wild, and On the Road. Beneath its slow tempo (j’aime bcp ce type) and frequent wide, high-angle shots, it hides countless reflections on the ultimate questions of life, as well as metaphors drawn from literary and philosophical classics.

The depiction of death is particularly striking. Watching Chris’s final moments—the fragile, erratic heartbeat, the overwhelming flood of light perception, the blurred will, the hallucinations, the helpless incompleteness—was deeply shocking. It was eerily close to what I’ve always imagined death to be.

Every young person despises chains, worships freedom, and dreams of detachment. But what exactly are the boundaries of chains? How do we define freedom? And what supports detachment? The film weaves lyrical techniques—Western folk guitar, a chapter-like structure, quotations ranging from Jack London’s The Call of the Wild to Thoreau’s “Rather than love, than money, than faith, than fame, than fairness, give me the truth.” But what “truth” is Chris really seeking?

He believed that by breaking rules and fleeing human civilization, he could find the essence of life. He gave himself endless psychological cues, dressing up his escape as a pursuit of some higher essence, rather than what it really was: running away.

In reality, he may have been just a spoiled child, disillusioned with his parents, rejecting his family and society—the archetypal beat generation drifter. He never seriously calculated the cost of his choices.

Gifted and privileged, he never truly faced hardship. He scorned the rules of society not out of moral clarity, but because he had never truly confronted his own inner self. He deliberately dodged every question about his parents. He fled from the trust of the farm owner, from the friendship offered by the drifter couple Jane and Rainey, from the love of the guitar girl, from the fatherly affection of the old leather worker. He created for himself an absolute existence, convinced that Alaska was his final Eden, the ultimate form of self, a utopia unsullied by human noise.

That’s why Chris is far from a purely “realistic” character—every person he meets has symbolic weight. (The young couple in the Grand Canyon, then Jane and Rainey, and later the way he recalls his parents, hinting at an evolving view of love and marriage, mirrored again in his interaction with the young girl played by Stewart.) To me, it almost has a religious undertone, reminiscent of The Alchemist: every coincidence feels guided by a God plan.

The irony is that the very authors Chris idolized—Thoreau, Tolstoy, London—spent their entire lives trying to flee the mundane world. Tolstoy embraced asceticism, lived most of his life on his estate, and at 50 suddenly fled, only to die miserably at a train station inn (like the protagonist of The Moon and Sixpence). Thoreau isolated himself at Walden Pond. London chased gold, did time, sailed, reported, traveled the world. Chris longed for their lifestyles but overlooked the one crucial element: the lived experience and survival skills underpinning them.

When he butchered the moose poorly and panicked, when he failed to identify edible plants and poisoned himself, he finally realized he was just a naïve, incapable kid. The freedom he idealized wasn’t nearly as beautiful in practice as in his imagination. His romanticized vision blinded him to the practical necessities of survival.

So this film serves as a mirror for every young dreamer who yearns to cry out “Give me liberty!”—and also for those suffocated daily by the routines of society, offering the kind of existential jolt one gets from The Catcher in the Rye. But in the end, the road is ours to choose. As one philosopher said, “The opposite of correct is error, but the opposite of truth is often another truth.” Freedom versus planning, self versus service, nature versus modernity—there is no single correct answer.

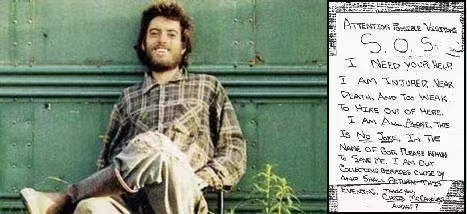

And yet, when Chris’s tears fell, and he scrawled with his last strength: “Happiness only real when shared”—he finally faced himself. He realized that selfishness was the root of all his troubles. Happiness is born from self-knowledge, but self-knowledge requires sharing—sharing joy, pain, sorrow, and love with others. Family, friendship, romance: solitude was never transcendence, only escape. He no longer needed to flee, no longer the extremist who hated civilization. He began to understand that “to call each thing by its right name” was to see that every being has its place and destiny. His final signature—“Christopher Johnson McCandless”—was no longer “Alexander Supertramp,” the supposed hero who broke free of cages. His unreachable ideal had come full circle, back to the embrace of his parents.

“What if I were smiling, and running into your arms, would you see then, what I see now?”

Toutes choses sont sorties du néant et portées jusqu’ à l’infini.

We often oscillate endlessly between two opposing truths, only to end up in the very truth we despised in our youth.

The old leather worker once told Chris something along the lines of, “You should know God exists—though perhaps you wouldn’t call Him that.” And in his dying moments, crawling to the highest place he could reach, gazing at the sky, Chris finally found his God. Just as he wrote in his farewell, God saved him—not by life, but by death. In that blinding light of the sky, his will fading, he returned to his parents’ embrace. Resting on their shoulders, he looked ahead, understood the world, and was finished.

链接: https://pan.baidu.com/s/1hCKQT4j6leNDZqG38SitQw?pwd=2048 提取码: 2048 (生肉)